Disclaimers

- This is my first blog post

- This is simply for my own enjoyment, take from it what you please.

Research shows that the most common questions in early social interactions are those that aim to identify shared context, typically in the form of identity-establishing questions like

What do you do?

Usually when I tell people I study physics, the typical response is a puzzled look of confusion, or something like “that sounds difficult.” The idea of physics as a mysterious, esoteric field is fairly common. Some may read about it on occasion, catch bits of information in the media, or may have even taken a class at some point, learning Newton’s laws of motion and how to apply them. Most, however, have little notions of what physics is or what it means to do physics. But at some point or another, we have all wondered about the world around us. Be it as a child learning how to operate in the physical world, or as an adult looking at the stars in the night sky, wondering what lies beyond. This is what physics is about — understanding the universe around us.

A follow up question is usually something like

What do you plan to do with that?

My usual response is along the line of, “I’d like to do research.” Again, I’m met with a puzzled look or a question like “so where will you work?” Admittedly, this answer is a bit vague. “Research,” is not a career in the traditional sense. Often times, they are not really sure what it means to do research. This line of questioning is ultimately trying to get down to the real question of, “who are you?” However, my answers are often unsatisfactory, because as with most PhD students, I simply don’t know what career I will have. During your PhD, you are absorbed in your field of interest, and the work is largely academic. If you want to continue this kind of work, you would likely go on to into academia, taking a faculty position at a university. The positions are relatively sparse, and so a large percentage of us will wind up in the vast world of industry. What this means is widely varying and depends on your field of study and what skills you’ve acquired. Typically for scientific domains, this will involve some sort of data analysis or R&D position. I personally make efforts to avoid overthinking it. I enjoy doing research, and I’d like to continue as long as I can.

The sequence of exchanges I’ve just described is a common and recurring one. So, what I aim to do in this post is share a bit about what I do. If you’ve stumbled upon this post as a non-physicist hopefully you will find it interesting, or if you are a physicist, maybe you can still enjoy my musings.

What is condensed matter physics?

I am not going to provide an overview of the field of physics as a whole. I’d like to make the more modest attempt at describing the area of physics that I study, “condensed matter physics.” Condensed matter physics is the largest subfield of physics, and is a wide spanning landscape of different research topics. My objective is just to give a little picture of what it means to “do” condensed matter physics, and perhaps a flavor of what it aims to achieve.

The Wikipedia definition of condensed matter physics is:

Condensed matter physics is the field of physics that deals with macroscopic and microscopic physical properties of matter, especially in the solid and liquid phases, that arise from electromagnetic forces between atoms and electrons.

While this technically is an all-encompassing definition, it really doesn’t give a feeling for what it means to study condensed matter physics.

Aside

The phrase “condensed matter physics” was not coined until the late 1960s by Nobel Laureate Phillip Anderson. In fact, the story of condensed matter physics has a much longer history, deeply tied with the history of humanity. To see a summary of this history, take a look at my second blog post A Brief History of Materials.

Why do we study "condensed matter" at all?

For one, it represents the overwhelming majority of the world around us. Metals, wood, silicon, organic material, are all forms of “condensed matter” and play vastly varying and important roles in our lives. All of the examples I just listed are solids, but the study of condensed matter extends to gases and liquids as well. This does not encompass all of the phases of matter, for example plasma, like that in the sun, is yet another state of matter. More modern research has revealed additional states of matter — superfluidity, Bose-Einstein condensates, fermionic condensates, and still more being discovered — which often fall in the domain of, or at least overlap with, condensed matter physics. These more exotic phases are typically found in a lab or within stars. Most of the matter we interact with, however, is in the solid state, and this is the subject of the majority of condensed matter research.

On a practical level, the study of solids has been a successful enterprise that has lead to most of the technological advancements we have today. The building blocks of computers and modern electronics, the transistor, was invented at Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey through our understanding of the solid state. The development of the MRI machine required an understanding of the magnetic behavior of nuclei in materials and currently relies on a large number of semiconducting transistors to operate. Developments like lasers, solar cells, positron-emission tomography, televisions, radios (the list goes on) have revolutionized nearly every area of life and all started in a physics lab somewhere.

However, in my view, the most fascinating reason to study condensed matter physics is that it tells us about the universe. Materials provide an accessible laboratory for us to explore the underlying laws governing the universe as a whole. We, and the matter around us, are not exempt from these laws. The questions about the very nature of reality can be sequestered in the behaviors of rather mundane materials, and within us. The attitude of many physicists, and myself for the most part, is one of indifference towards the practical uses our research has in the “real world.” Of course, if it happens to lead to a new revolutionary technology that makes the world a better place, all the better. But the reality is, most of the research we do only has implications within our narrow fields of interest. We will all argue, of course, that our research is in fact not so narrow, and represents an important facet of reality. If we’re lucky, it will influence a number of other research projects, which influences others, and so on, which will hopefully accumulate to a better understanding of the world. The main driving force for myself, however, is personal enlightenment and the art of doing science. Science is a beautiful symphony of minds coming together to create something where there wasn’t before. This “something,” however seemingly tiny it is, in the end reflects a truth about the nature of reality. The very fact that it exists, and that we are able to find it, is one of the deepest mysteries of all.

But what do you do?

Okay so after my rant about what condensed matter physics is and why its important, that still doesn’t explain what a condensed matter physicist does. The answer depends on who you ask.

All domains of physics research are roughly separated into theory and experiment. If you approach an experimental condensed matter physicist and ask, what do you do? They may answer by telling you there is some material of interest that has potential for real-world applications or may reveal something interesting about physics. This material is something that is physical and tangible, since experiment is in the business of measuring. They may then tell you that they begin by growing or manufacturing the material they are interested in investigating, and preparing the relevant conditions for observing something about the material. Once the material is in its proper configuration, they make the appropriate measurements to reveal some properties about the material. These measurements are then compared to established or suggested theories, and may suggest potential applications for future technology.

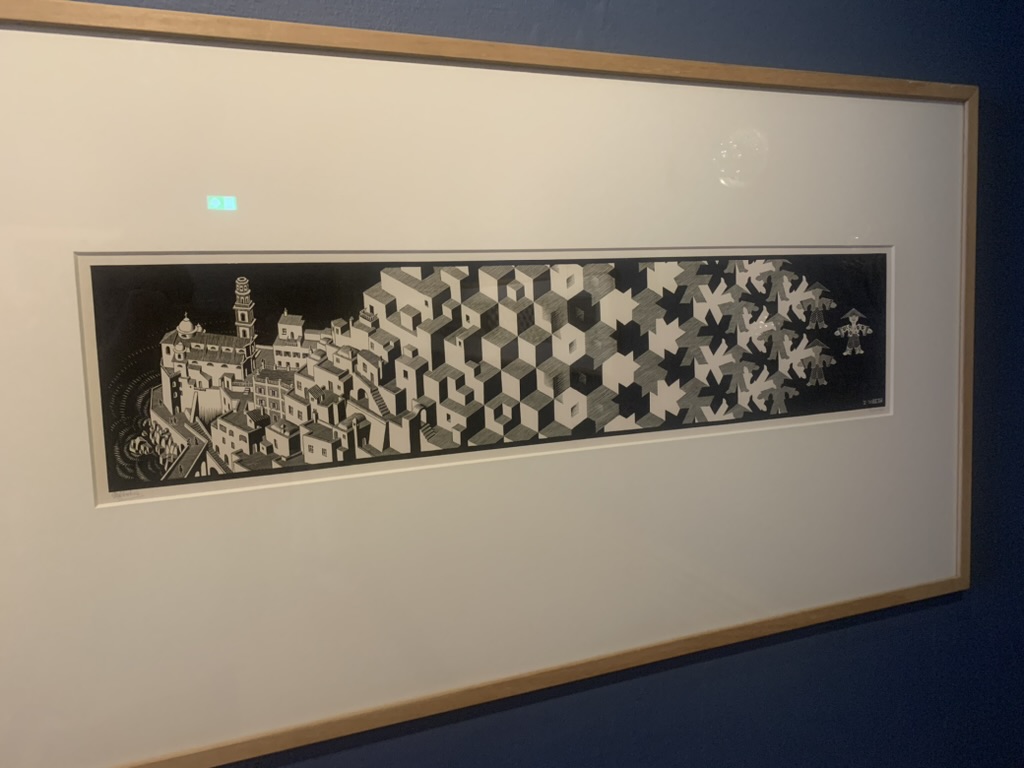

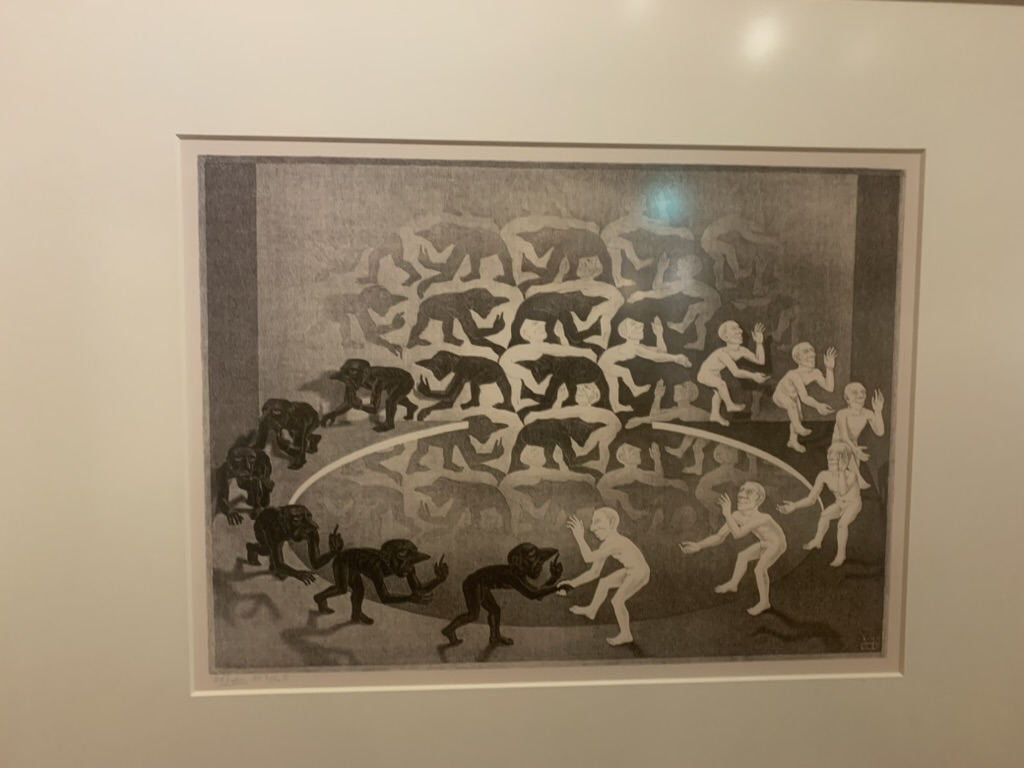

If you ask a theorist, like myself, we would say that we first begin by establishing a model for a system of interest. This system may be a material, or perhaps a device for a new technology. The picture below is one I took of one of M.C. Escher’s paintings at the M.C. Escher museum in The Hague, Netherlands. Creating a model of a material is a bit like this. We start with the actual material, and gradually abstract it down to a simple picture that we can understand. The model should retain the essence of the original material, capturing its essential characteristics. This is the art form of doing physics.

Escher

The rest of the pictures I post here are all M.C. Escher’s original artworks. He really had a knack for visualizing some of the themes in physics. I may make another post about it someday.

The model could be based on well-established theories, or if one doesn’t exist, we try to invent one. Models in the end take the form of equations. The methods of solving these equations are through a combination of on-paper calculations or computer code written to solve the equations. The solutions come in the form of numerical data or functions that can be visualized in a plot. We compare the plots with experimental measurements to see if our theory is actually explaining something manifestly real about the world. This generates the cycle of research; experiments motivating theories motivating experiments and so on.

There are of course exceptions to this picture. In more mathematical research, experimental connection is not always made. Whether this has “real world” implications depends on if you believe that science will tend to find its way into society, or if mathematics lives in a real and independent world of its own, but that is a topic for another post.

But what do you do?

Up to now in my early research career, I have studied topological materials. This is a fascinating are of research, and I will try to give an idea of what it is about.

Matter comes in different forms. We are used to interacting with solids, liquids, and gases, so we are innately aware that the same substance can behave quite differently in different circumstances. The most familiar is water; it can be liquid, it can become ice when cooled below its freezing point, or it can become gas when heated above its boiling point. This applies to other compounds as well. A physicist named Lev Landau generalized how matter undergoes these so-called phase transitions based on the symmetries it has. Water is disordered, but the molecules like to stick together through Hydrogen bonds. These bonds are relatively weak, so the molecules are almost free to move around as they wish. From the perspective of a water molecule, the environment looks the same regardless of where it is at, on average. There is no preferred direction or order in a glass of water. In the gas phase, water molecules are far apart and move independently. The environment is even more symmetric from the perspective of a water molecule in this phase; it is the same regardless of which direction you look. Ice on the other hand is less symmetric. A perfect piece of ice has a lattice structure, and is ordered in a crystalline pattern. In this case, the environment is only the same if you move in a certain direction by a certain distance.

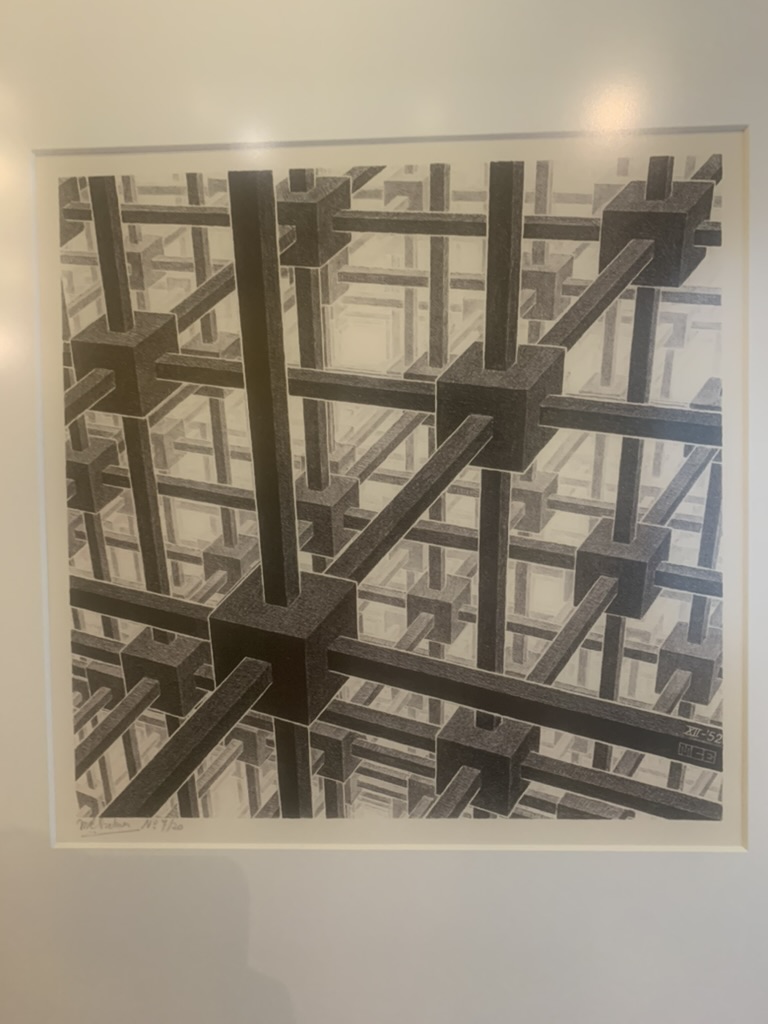

The picture below is another one of Escher’s artworks; it shows a crystalline structure. The lattice is periodically repeating, and if this were to extend beyond the frame, there would be no difference if you move, for example, from the center of one cube to another.

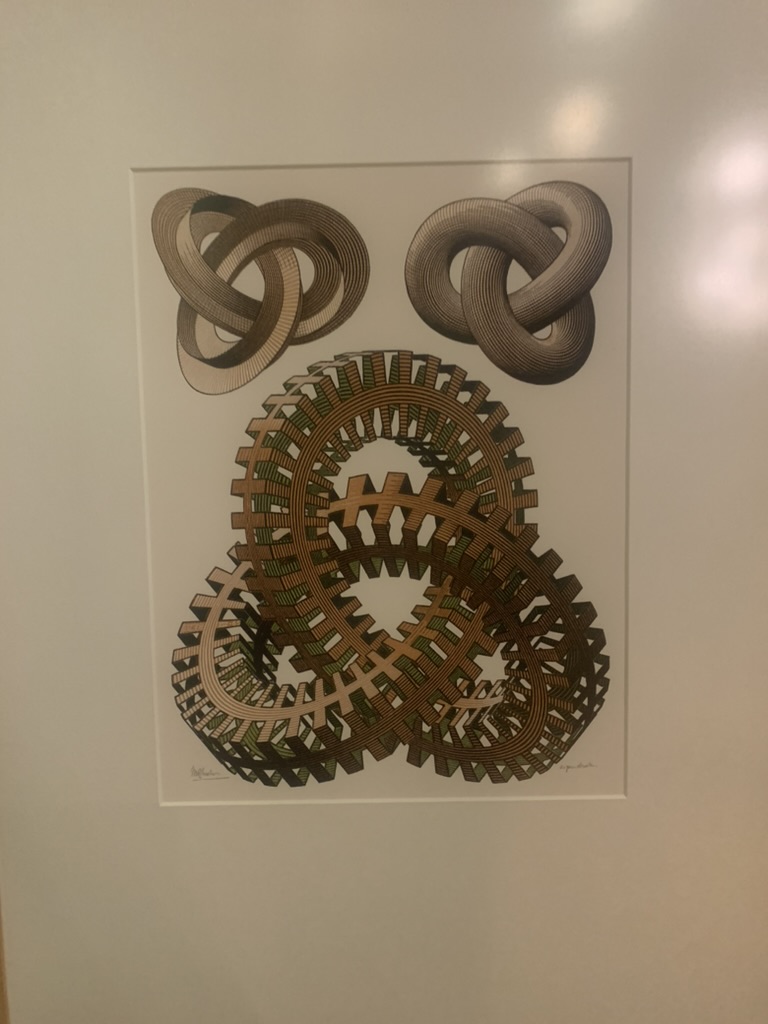

From Landau’s theory of symmetry, any two solids with the same symmetries and lattice structure are in the same phase. In the 1980s, it was discovered that two seemingly identical materials can exhibit very different behaviors. The root of this difference lies in something called the topology of the material. Topology is a branch of mathematics that studies objects that are deformed. A classic example of how topology works is by comparing a coffee cup and a donut. From the perspective of topology, these two are the same, as they both have one hole. You can deform the coffee cup to look like the donut, keeping the hole in the handle. Tearing new holes or healing old ones are against the rules. Another example is a belt. Twist the belt one full time, and glue the ends together. This is now topologically distinct from the original belt, since this twist cannot be undone without breaking the loop apart.

To understand what is really going on we need a detailed picture of how the particles interact. This picture goes by the name of quantum mechanics. Quantum mechanics became the prevailing theory for how particles behave sometime around 1900. When you look at particles closely, they behave very strangely. They are indecisive, and can be in more than one configuration at once, that is, until you look at it. Then it is forced to be in a particular state. The particles themselves are less like solid spheres that we might first imagine them as, and more like waves. These counterintuitive notions of how particles behave leads to some fascinating consequences.

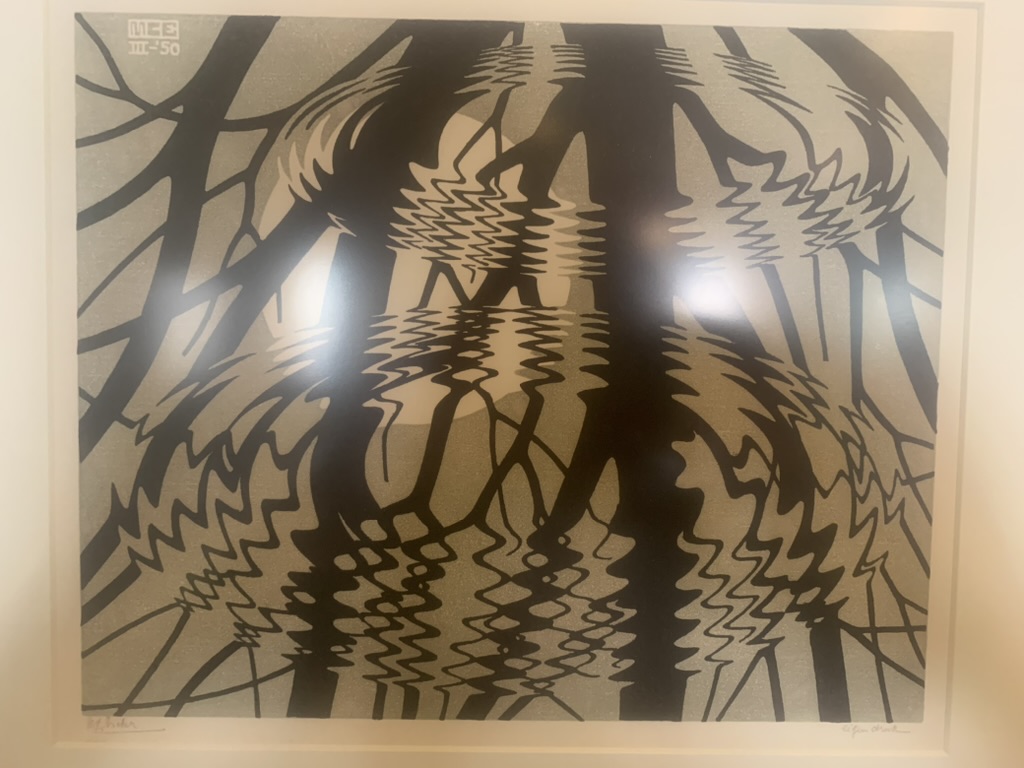

In crystalline materials, like solids, the state of the electrons may have a similar winding property as the belt. This is without any influence of the environment or observer. It is just a property of the material. This twist is what makes it topologically distinct from other materials. A non-topological material is as if you took atoms from a box, and placed them one by one into the crystal lattice structure. One of the consequences of topology, for example, arises in topological insulators. The material doesn’t conduct electricity in the bulk, but along the border it does so perfectly. The electrons propagate along the edges of the material in a chiral fashion. This means they move along a one way street, bypassing any obstacles in their way.

But what do you do?

In an average week, I spend about 80 percent of my time at the computer (I need to get outside more). The majority of this time is spent writing and analyzing computer code. Writing code means I write instructions for the computer to do something, solve some equations, and do something with the results. A good portion of writing code actually means rewriting code I had previously written so that it is more efficient and perhaps usable for others. As I write, I try to include documentation explaining the code for future readers as much as is reasonable. Almost as much time, if not more on some days, is spent finding bugs in the code where it doesn’t work, and fixing them so I get the results I expect. The end result is a set of nice looking plots to appear in a paper to summarize the findings. The remainder of my time is roughly evenly split between meeting and discussing the results with my advisor, preparing and giving talks at meetings and conferences, reading research papers or textbooks for my courses, solving homework problems, and, as we all do, procrastinating.

pie title Time spent "Writing code" : 30 "Debugging code": 20 "Meetings" : 10 "Talks" : 10 "Coursework": 10 "Reading": 15 "Procrastinating": 5

Is writing this a form of procrastinating?

Yes.

Did you undersell the percentage of time spent procrastinating?

Maybe.